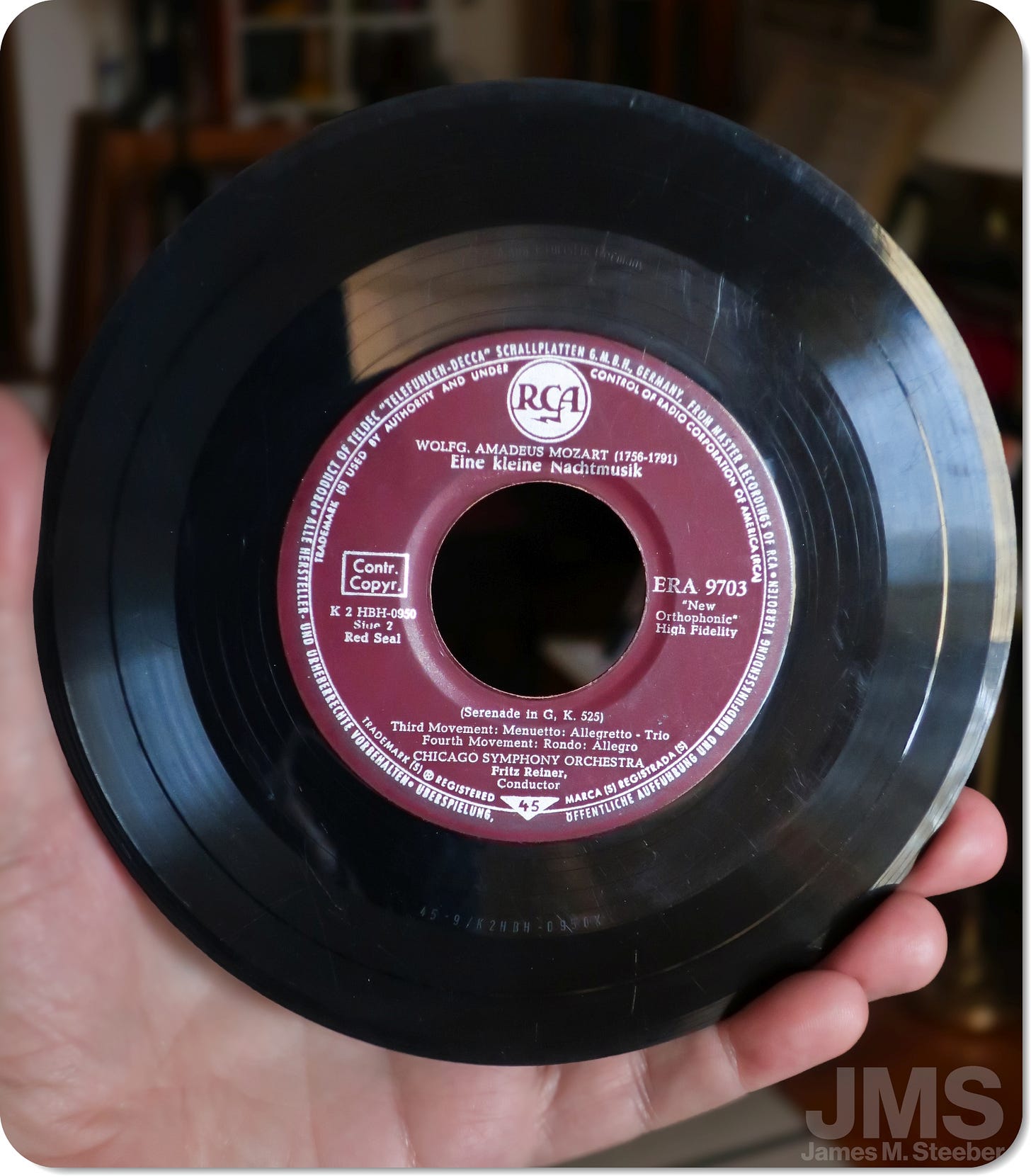

A few days ago I was watching a BBC documentary on the life and music of Mozart. The story eventually arrived at his very famous (sehr bekannt) Serenade No. 13 in G, K. 525, usually referred to as “Eine Kleine Nachtmusik”. Often when this piece is mentioned, I think back to the 45 rpm record I received from my father when I was a child. Actually it was part of a small stack of classical 45s encompassing a range of works. I played these discs throughout my young years, gradually damaging them on inferior record players. No matter. Most of them were German and Dutch monaural pressings, owing to our location in Aruba – a Dutch island. My father managed the one large hotel resort there. I was told that at some point these records had been used as background music in the dining room or maybe the casino.

The serenade, in four movements, was divided between sides 1 and 2 of the record (performed by Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony). I knew nothing of the origin of the music – when it had been composed or possibly even who composed it as I wouldn’t have been able to read the label. Just the same, I intimately knew the sound of the work by the age of 5 or so. It was deeply set in my mind and seem to represent some elegant place in the universe that in some way seemed to float. I saw patterns and forms in my head. It didn’t matter that the music had been composed about 180 years before it reached my record player. To me it simply existed and it became one of my most regal possessions.

Just having these records, being an only child, I had many occasions to play them. The discs included excerpts on a Fontana 45 of the Tchaikovsky piano concerto no 1, the Brahms Hungarian Dance No. 6, the Soldiers’ Chorus from the opera Margarete (aka Faust) by Gounod, L’Angelus de la Mer by G. Goublier and L. Darocher, Ave Maria by Franz Schubert, another Faustian soldiers’ chorus track, and the Barcarolle from Tales of Hoffman by Offenbach. There was also Solveig’s Song by Grieg (which I particularly loved) and a lush rendition by Dutch Cortot disciple Marinus Flipse of the C sharp minor prelude by Rachmaninoff. Another Philips 45 offered Johan Strauss Jr’s Emperor Waltz followed by Land of Hope and Glory by Elgar. There was yet another Philips 45 of the Stenka Rasin (aka Volga Volga) sung by a huge chorus and then a track of an uncredited piano solo (Marinus again?) of the Waltz no. 1 by Brahms.

Two more American 45s offered Kostelanetz’s excerpts of Puccini’s La boheme on sides 1 and 2. I remember that the introduction sounded like impossibly complex music to me, seeming to swim into oceanic folds of sound – astounding, really. Lastly, there was a Capitol 45 of Addinsell’s Warsaw Concerto played by the Hollywood Symphony Orchestra with Leonard Pennario at the piano and Carmen Dragon conducting. Most of this material had been recorded in the 1950s.

What a collection! They informed a rather romantic notion of the world while connecting me in a styllized sense to the world my father, a refugee, had left behind in Europe. There may have been some conscious intent in my receiving these records, as both of my parents wanted me to absorb art and music – actually, just about anything. Well I did. This emphasis on classical music is likely why the popular music of my time took longer to get to me. The jazz I knew was actually from live performances in the hotels, but a true understanding of that genre had to wait until my first trip to Europe.

Classical music had also come through a good pair of headphones. When I was about six, my father rigged up our Braun stereo to play through a SONY 4-track tape recorder, and one afternoon he offered to let me listen to something. “Be careful; it might be loud for you,” was his warning. I eagerly awaited the loud sound and heard the beginning of Beethoven’s “Kreutzer Sonata” with Heifetz, sounding like the violin was inches from my head. If anything, it was loud enough and also rivetting.

Eventually, as one might expect, classical music had a lot to do with my professional life. It continues to weave through my existence. In college I learned to accompany modern dance and ballet, on piano. I became a good improviser, and I eventually took this skill to New York and found work at Juilliard and Martha Graham (plus a host of other schools and companies). In 1993, I debuted a piece of my own at the 92nd Street Y and next year at the Kaye Playhouse. About four years after that I became a coordinator and later director of the classical artist program at Yamaha Corporation of America. That was about thirteen years of work. I found myself laid off somewhat into the economic global banking credit crisis and discovered that a similar job was nowhere to be found.

Gradually I came back to the music and dance world and felt strangely at home. Aside from other sidelines in graphics and photography, I was back at the piano, feeling as if I had left the dance world only weeks before, even though it had been seventeen years. The corporate world had offered comforts and periods of security and adventure, but it could not be depended to last or for that matter even satisfy artistically. It was a hard lesson to accept at the time of my last day.

To start, I had a few rounds of piano lessons when I was five – sitting down with a cocktail pianist at the hotel in San Juan. I still have the Thompson book we used. According to letters of the time he gave my mother stellar reviews, but circumstances ended the lessons. At home I had a little electric reed organ with chord buttons on the side – hardly the on-ramp for expressive piano pieces. We finally settled in the States when I was nine, and one of the first acquisitions was a big used upright piano. Lessons followed almost immediately with a nice elderly woman (Mrs. Bowman) who had me learning from Michael Aaron books on her girlhood Steinway. Again, raves from the teacher that I was learning like an adult. I was actually catching up for lost time.

I studied with various teachers in various living rooms until college, and then I found my way (past the photojournalism I had chosen) to the piano again via dance accompanying, where I studied with a brilliant improviser named Eileen. It was an unconventional course of study, and I’m still making up for lost time, still surprised at what I can do and how I can learn.

Back to the records – they were the key to orienting me. An only child, I spent so many hours over the years just having them play without interruptions. As I grew up, there were even found records from dumpster dives (bringing in classic Broadway musicals and standards that I’d never heard of) and my parents’ own classical record collection which included mysteries of its own. All of this stoked my imagination and gave my world more depth.

Early influences are vital to a good inner life. Some years ago I discovered a small reel-to-reel audio tape, the kind our family used to send like letters between the States and the Caribbean. On the tape I’m about two and half years old. My mother is showing me off for the microphone, and she begins to sing lyrics to George and Ira Gershwin’s “Summertime”. She sings half a line, and I finish the phrase – speaking the words. At one point I finish the demonstration by uttering “…with Mommy and Daddy standing by”.

I was astounded by this act my mother and I had rehearsed, as I had no recollection of it. Just the same, Porgy & Bess still includes some of my favorite music, and that does include “Summertime” which my mother would often sing to me as we put out the light. I still play it in dance technique classes, as it makes a perfect adagio. The early influences again take root.

My point is this: These early years of life form the very soul of it, releasing their bounty all through one’s existence. The musical experiences I had, just listening to these discs, gave me the gallery and the concert hall I carry around to this day.

JMS February 2025

(André Kostelanetz: two minutes of side one of his 1955 Puccini “La Bohème” Columbia 45. I found the music astounding and incomprehensible as a child.)

Really enjoyed this one. Thanks, James.